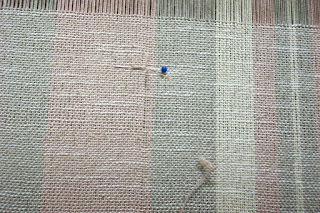

knot in warp - repair end threaded through same heddle, woven together with original end for 1 to 1.25", then cut original end and continue weaving until...

original end is long enough to re-thread through the heddle. Weave 1 to 1.25", then cut repair end. Clip all tails once cloth is off the loom before wet finishing. No sewing required.

This warp is reminding me that just because something is 'simple' doesn't mean it's 'easy'.

There is a reason so many testing/learning programs concentrate on the execution of a good plain weave. While the thread interlacement is 'simple', making it good is much, much harder. Every little inconsistency will show up.

How do you get better? By first of all training your eye to detect those pesky inconsistencies. By listening to your loom, yarn and most of all, your body. Weaving is a biofeedback activity. It has to be because you are using equipment and tools and you need to be able operate the equipment and handle the tools with skill. And by that I mean obtain the results you desire through the use of those tools and equipment.

People who don't weave don't have a good grasp of just how skilled you have to be to make good cloth. Especially good plain weave.

The first step in achieving a good plain weave is to learn how to wind and beam the warp under consistent tension. There are many different processes that people employ to do this - it doesn't matter which you use so long as you have a warp that is consistent on the beam. In my studio this means beaming the warp with fairly high tension, using firm warp packing (unless I'm sectional beaming on the AVL in which case the warp is beamed with high tension and no warp packing).

The warp must then be tensioned for weaving - again, consistently. Unfortunately this is easier said than done because when the fell is advanced and tension reapplied it is nearly impossible to achieve precisely the same tension as was previously used. Looms with finer adjustments (two 'dogs' rather than one, for instance, smaller teeth in the pawl for another) are easier to reset. So the weaver has to replicate as closely as possible the tension on the warp each time the warp is advanced. And then s/he has to adjust their beat to compensate for the different tension on the warp. This becomes more difficult on a long warp as the cloth is being woven, building up on the cloth beam. Instead of a nice hard surface, the cloth beam becomes padded with layers of woven cloth. In addition the ratio of the diameter of the warp beam to the diameter of the cloth beam continuously changes.

The weaver has to train their eye to spot inconsistencies so that s/he can see what is happening, analyse why it is happening, and know what and how to adjust what they are doing to get the results they desire.

They must pay attention.

They must be able to handle the shuttle in such a way as to leave the appropriate amount of slack in the weft so that there is appropriate draw in. If they choose to use a temple, they need to know how to most effectively apply that. They must know how to wind 'good' bobbins and control the feedoff of yarn from the bobbin.

Again I say, pay attention.

Pay attention to their equipment, their tools, their results. Spot errors immediately and fix them to avoid unweaving or worse, have to fix them off the loom.

Once a weaver has mastered plain weave they will have achieved a level of skill or competency that will bring them a long way towards understanding the subtlety of the craft and a level of mastery that will make weaving less stressful and more enjoyable. They will even be able to function with just surface attention so that they can have other thought tracks running alongside of their weaving. But their eye and their body will know what to do and as soon as an inconsistency crops up, the weaver will be able to deal with it efficiently. Mistakes will happen, but they won't be the end of the project.

Most things in weaving can be fixed, one way or another, depending on how much time one is willing to devote to the fix. Some things aren't 'perfect' but don't really do much harm. I know my beat isn't perfect in this cloth but I'm also working with a slub yarn which makes achieving a 'perfect' beat pretty nigh impossible. And ultimately it's a tea towel. I'm not submitting it for jurying. I just want to make something 'nice' for people to dry their dishes. These will do just fine - even though they aren't 'perfect'.

Sometimes the best lesson to learn is when to let go of perfection.

3 comments:

Thank you Laura!

Thank yoh for the wonderful information and the lesson! I neede this remi der about perfection! :)

"Once a weaver has mastered plain weave they will have achieved a level of skill or competency that will bring them a long way towards understanding the subtlety of the craft and a level of mastery that will make weaving less stressful and more enjoyable."

This is so true! Plain weave is the most difficult weave structure to master. To get the desired sett, beat, nice selvedges, consistent cloth from the beginning of the warp to the end are skills that separate the beginner from the master. What seems so simple, one thread crossing over another is not simple at all.

Thanks Laura for your excellent post, there is some really useful advice here! As I am just about to make the jump from table loom weaving to floor loom this is really relevant to me right now. 😀

Post a Comment